by the Rev. Thomas Ferguson

I was teaching a class session once on the English Reformation, and, as part of breaking down the different ways Elizabeth I’s reign helped shape and define what we know as the Church of England, we had a discussion on the Thirty-Nine Articles. I went through the history of their drafting and adoption; talked about the Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed influences in them; and noted where they were clear and where they were masterfully ambiguous. I then asked for questions. One student raised a hand and asked, “Do we have to know this?” It was not the question I had been expecting, I had thought maybe people were unaware of what supererogation was. “What do you mean?” I replied. “Well,” the student said, “does The Episcopal Church require us to know or believe this, and, if not, why are we studying it?”

That student had innocently stepped right into the middle of the broader and more complex issue of the role and function of the Thirty-Nine Articles in The Episcopal Church. As part of this Thirty-Nine Articles Project, in this opening salvo we will look at precisely that question.

In giving an overview of the place and role of the Thirty-Nine Articles in The Episcopal Church, it is important to note the way in which The Episcopal Church has a rather doubly distinct position with regards to confessional theological statements. In the first case, as a member of the Anglican Communion and shaped by its theological and ecclesiological inheritance from the Church of England, The Episcopal Church likewise shares a common Anglican perspective on confessionalism. The Church of England, and subsequently the members of the Anglican Communion as it developed, do not hold to doctrinal confessionalism in the same ways as churches of the Reformed or Lutheran traditions. This is not to say that the Thirty-Nine Articles have not been an important doctrinal touchstone, nor that the Articles do not function in a binding manner in some provinces of the Communion: only that they do not function in exactly the same way as, say, the Augsburg Confession does within the Lutheran tradition.

While standing in that same shared tradition, The Episcopal Church also has had a different history with regards to the Articles as compared to other provinces of the Anglican Communion. For one, since The Episcopal Church was disestablished in the 1780s when colonies began to rewrite their state Constitutions, and since the Bill of Rights forbade Congress to establish a particular religion, the Articles never served any kind of broader civic role. For instance, given the established nature of the Church of England, subscription to the Articles were required at Oxford University and Cambridge University well into the 1800s.

But perhaps most significantly, the Articles were never specifically adopted as a doctrinal standard by The Episcopal Church, nor was subscription to the Articles required in any way. This is a second distinctive aspect of The Episcopal Church’s relationship to the Articles. While no longer required for enrollment in universities or for the basis of what we would consider civil oaths, nonetheless the Articles are still part of the oath clergy swear at ordination in many provinces of the Communion.

The Episcopal Church adopted a Book of Common Prayer, Constitution, and initial set of canons at the second General Convention held in 1789. The Constitution of 1789 stated that:

A Book of Common Prayer, Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites arid Ceremonies of the Church, Articles of Religion, and a form and manner of making, ordaining, and consecrating Bishops, Priests, and Deacons, when established by this or a future General Convention, shall be used in the Protestant Episcopal Church in those States, which shall have adopted this Constitution.

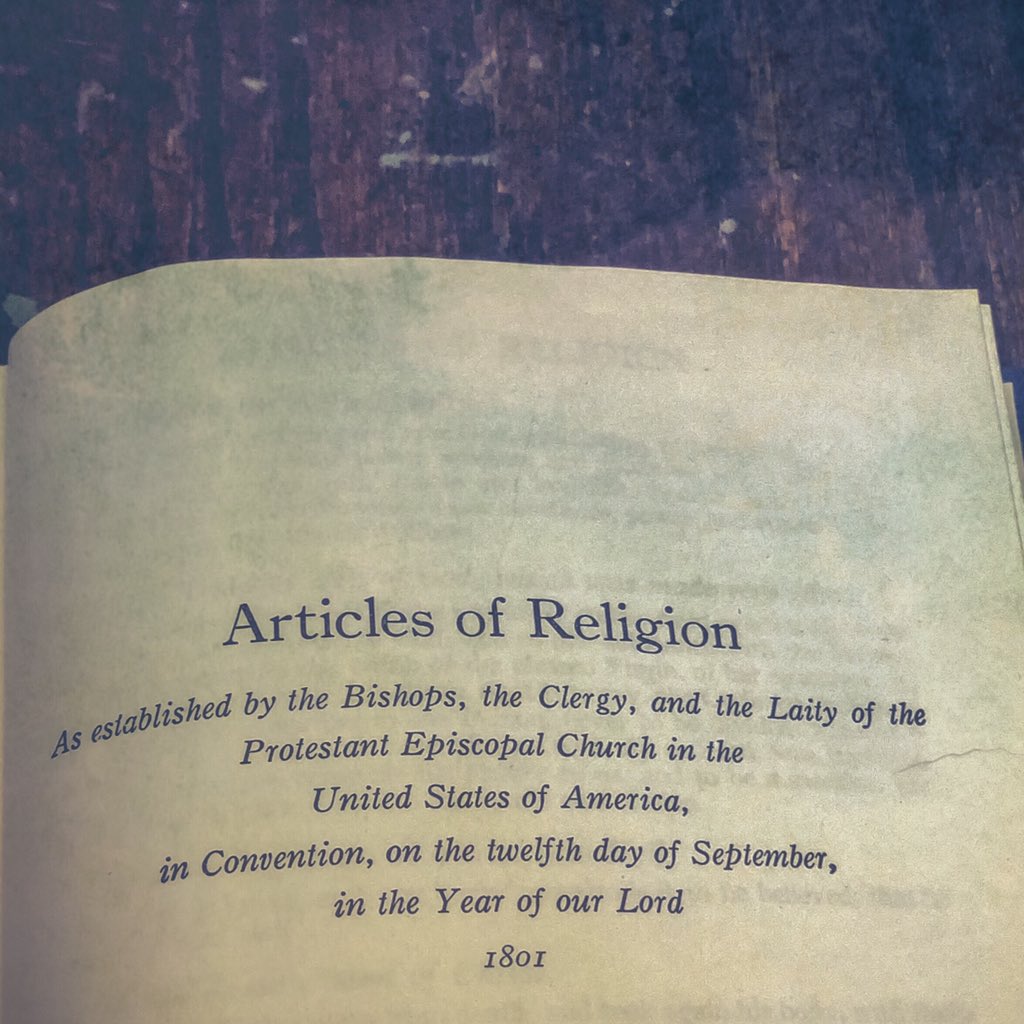

Twelve years later, the General Convention finally got around to addressing the question of the Articles of Religion. The 1801 General Convention declared that the articles of religion are hereby ordered to be set forth with the following directions to be observed in all future editions of the same [i.e., the Book of Common Prayer]; that is to say following to be the title; viz. “Articles of religion, as established by the Bishops, the Clergy and the Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, in Convention, on the 12th day of September, in the year of our Lord 1801.

A slightly edited and amended version of the Thirty-Nine Articles was thus “established” by the Convention. However, nowhere in the Constitution or Canons did it explain what “established” or “shall be used” meant.

Perhaps seeking some clarification, a proposed canonical change at the 1804 Convention would have included the Articles of Religion in the declaration that clergy were required to sign at ordination (currently Article VIII of the Constitution, in 1804 this was then Article VII). The proposal was not passed. As the minutes of the Convention note,

A proposed canon, concerning subscription to the articles of the church, was negatived, under the impression that a sufficient subscription to the articles is already required by the 7th article of the constitution.

It would thus seem it was the mind of the Convention that the promise to conform to the “doctrines and worship” at ordination already incorporated the Articles of Religion – however this understanding is captured only in the minutes, and was not part of any resolution or canonical action of Convention.

The Articles were printed in subsequent printings of the Book of Common Prayer, between the Psalter and the Ordinal until the 1892 Book of Common Prayer. In the 1892 and 1928 Books of Common Prayer, they were printed at the end.

The 1871 General Convention included an examination on Articles as part of the requirements for preparation for ordination, a requirement which lasted until the 1904 General Convention, when it was removed.

The next significant discussion of the Articles takes place at the 1907 General Convention.

The 1907 General Convention received a proposal to amend the Constitution to remove the clause mentioning the Articles of Religion from Article X of the Constitution. William Reed Huntington, driving force behind the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, presented the legislative Committee’s report. The Report notes that “Precisely what standing the Articles enjoyed in the American Church during the first years of its post-revolutionary revival it is difficult if not impossible to say.” It further goes on to argue that “The whole ecclesiastical sky has changed since the Articles were originally imposed upon the Church of England…In a word, the Articles are antiquated without being ancient.”

These concerns about being “antiquated,” are in part, tinged by the anti-Catholicism common at the time. What the Committee has in mind here is the introduction of papal primacy at the First Vatican Council in 1870 and the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary promulgated in 1854. If the Articles are to counter the errors of the Catholic Church, then they are not effective anymore, since there are new, post-Reformation Romish errors needing correction.

The Report questions the inclusion of the Article in the Book of Common Prayer:

This state of things tends to demoralization of both the Clergy and the Laity. Of the Clergy since it leaves them helpless to answer with any definiteness the question, What is the Doctrine of the Episcopal Church? Of the Laity because they are thoroughly perplexed by the sight of what looks to be a Creed supplementary to the other Creeds, while at the same time they are assured by their spiritual guides that it is something about which they need not at all concern themselves. Why should it be here in the Prayer Book, they ask, if it be unimportant? Why, if it be important, should we be told that as Laymen we need not care?

Lastly, the Report argues, “The Articles are a bar to Church Unity both at home and abroad; at home because they constitute a wall over which we have to talk with our neighbors at a great disadvantage, abroad because in the great Church of the East which holds passionately to the Nicene Faith, their very existence is unknown.”

Despite the Committee’s report and recommendations, the House of Bishops did not consent with the House of Deputies, and the commission to revise the Articles was not established, nor was Article X amended to remove mention of the Articles.

The question of the Articles came up again in the process leading towards revision of the 1928 Book of Common Prayer. At the 1928 General Convention, numerous proposals were presented for dropping or revising the Articles as well as for their continued inclusion in the Book of Common Prayer – including one petition which claimed to have 34,057 signatures in support of continued inclusion of the Articles. None of the competing proposals were adopted, and the Articles were printed in the new Book of Common Prayer with the same prefatory language, unchanged since 1801.

In the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, the Articles were included in a section titled “Historical Documents,” and, by doing so, perhaps continued to muddle the situation. Not all of the documents in the historical documents section would seem to be of equal authority. For instance, the Chalcedonian Definition has never been used in worship as, for example, the Nicene and Apostles’ Creed. The Athanasian Creed used to be used in worship, but is no longer, yet is included in the Historical Documents section. The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, while included in the historical documents section, actually derives authority not from that placement but because of the numerous times it has been reaffirmed by the General Convention of the Episcopal Church (more than nine different times).

The 1988 General Convention removed whatever ambiguous authority the Articles might have claimed. An amendment to Article X of the Constitution was passed on a second reading, shortening the official title of the Book of Common Prayer:

Resolved, That the first sentence of Article X of the Constitution is hereby amended to read as follows:

The Book of Common Prayer

and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating Bishops, Priests and Deacons, the Form of Consecration of a Church or Chapel, the Office of Institution of Ministers, and Articles of Religion,as now established or hereafter amended by the authority of this Church, shall be in use in all the Dioceses.

RIP, ambiguous meaning of what “established” and “shall be used” meant with regards to the Articles: 1801-1988.

The last time the Articles would be the focus of discussion at General Convention as a kind of doctrinal standard came in 2003, at the same Convention considering giving consent to the election of Gene Robinson as Bishop of New Hampshire. Resolution B001 was submitted, which proposed, in part, specifically affirming two of the Articles of Religion:

Resolved, the House of Deputies concurring, That the 74th General Convention affirm that “Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation: so that whatsoever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should be believed as an article of the Faith, or be thought requisite or necessary to salvation,” as set forth in Article VI of the Articles of Religion established by the General Convention on September 12, 1801; and be it further

Resolved, That the 74th General Convention re-affirm that “it is not lawful for the Church to ordain [that is, establish or enact] any thing that is contrary to God’s Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another,” as set forth in Article XX of the Articles of Religion established by the General Convention on September 12, 1801;

Some saw the Resolution as an effort to try to deny the authority of the General Convention to consent to the election of an openly gay man as bishop, largely because of the following resolved clauses in the Resolution:

Resolved, That the 74th General Convention affirm that every member of this Church is conscience-bound first of all to obey the teaching and direction of Our Lord Jesus Christ as set forth in Holy Scripture in any matter where a decision or action of this Church, or this General Convention, may depart from that teaching; and be it further:

Resolved, That the 74th General Convention affirm that councils of the Church have, and sometimes will, err but that Our Lord Jesus Christ, present through the person of the Holy Spirit, can and will correct such error…

The resolution was defeated, 84-66, with 8 abstentions.

So we return to the original question the student asked: “Do we have to know this?” On the one hand, it is clear that the Articles were never formally adopted as any kind of doctrinal standard with any clarity. It is only from 1871-1904 were they specifically named as something clergy should be examined on for ordination. On the other hand, they were certainly a part of many seminary curricula and a number of manuals and books devoted to the Articles were common in the 19th and early 20th centuries: at one point the trustees of the Virginia Theological Seminary, for instance, required students to memorize the Thirty-Nine Articles.

As we look towards the 21st century, perhaps in a sense we can return to that Report from 1907 General Convention. Though its proposals were not accepted, the report asked a pertinent and valid question: if the Articles helped shape and define Anglicanism in a particular context, do we need to ask ourselves how we shape and define Anglicanism for our own context? In this sense, the Articles could become not an ends, but a means; not only a touchstone, but a resource; not antiquated, but a living legacy.

The Rev. Thomas Ferguson, PhD, is Rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Sandwich, MA, and Affiliate Professor of Church History at Bexley Seabury Seminary.

I need to vent. Yes, we should know and understand the 39 Articles of Religion. To not know them is sheer laziness. It’s no wonder the Episcopal Church is splintered. I’m trying to find a church in Atlanta. So far, each one has thrown The Book of Common Prayer out of the window. The sacrament of Holy Communion is printed on a bulletin. I think the final straw came yesterday. My husband and I visited yet another church. Of course the service was printed in the bulletin. The General Thanksgiving was different, which I know is permitted. However, when I saw the service skipped over the Confession, Absolution, Consecration, Oblation, Invocation, and The Lord’s Prayer, we left. How can this be?

I have never attended an Episcopal Church that abbreviated the service. I would be shocked if any church in The Diocese of Atlanta did. That being said, in my experience, the confession is usually left out of the service during the Easter season and is included again beginning on Pentecost Sunday. As for the use of bulletins, I think it is just to make the service easier to follow along for those unfamiliar. My parish, Grace in Gainesville, prints certain prayers/readings in the bulletin but not the whole service. The parts not printed are still included in the service. I wonder if you had stayed you may have seen that the liturgy was complete. May I ask what parish it was?

Nora, come try Holy Trinity Parish in Decatur, where I serve. We’d be thrilled for you to join us for worship, and we are a Prayer Book parish in word and deed and spirit. Reverent, joyful, traditional services. Our bulletin has page numbers referring to the prayer book— you’ve got to open up the BCP. Rite I at 8:00, Rite II at 10:30. I’d be glad to answer any questions you have.

Nora, come worship with us at Holy Trinity Parish in Decatur, where I serve. We are a prayer book parish in word, deed, and spirit. Our bulletins have page numbers to reference the BCP, and you’ve got to open the prayer book and hymnal. 8:00 Rite I, 10:30 Rite II. Worship is joyful, reverent, traditional, and rubrically compliant. We’d love for you to pray with us; let me know if I can answer any questions.

The insight of the final paragraph is the fundamental impetus of Henry Newman’s Tract 90. Here might be a template for our own engagement that takes the Articles seriously while not raising them to the level of credal statements and opening debate to the insights of post denominational engagement.