by the Rev. Porter C. Taylor

Like many elements of Anglican theology and practice, the 39 Articles of Religion are often used as a means of division rather than having a unifying effect. You can divide Anglicans into any grouping you desire (i.e. High, Low, and Broad or 4 streams, or Anglo-Catholic, Reformed, Evangelical, and Classical etc. etc.) and you will find the 39 Articles at the core of each grouping. It is not that the Articles are a driving factor in the distinctives and charisms of a particular Anglican sub-set, but that one’s churchmanship often drives how one reads, interprets, and values the Articles.

Let the reader be warned from the outset: this blog series is not designed to value or highlight one reading over another. This is not a series for Anglo-Catholics, Reformation Anglicans, or cradle Episcopalians. This is a blog for anyone who is an Anglican Christian and is looking for a resource to accompany their reading of the Articles. In particular, this introductory post will not settle anything but rather seeks to provide a lens through which or a framework by which we read this historic document together.

One of my mentors in the earliest days of my ministry training, Bishop Fitzsimmons Allison, would often remark that, “Those who think the English Reformation was about King Henry’s marriage(s) deserve Henry.” I believe we should add to this statement that such people would also be deserving of Henry’s 6 Articles.

As with many elements within Anglican thought there is little to no agreement as to what the Articles are, what they mean, or why they matter. To quote the famous philosopher, Humpty Dumpty, words can mean anything we want them to as long as we “pay them enough.” Sadly, or perhaps confusingly, the language of the Articles has been paid a great price by every stripe and corner of the Anglican Communion and extant are a plethora of interpretations, applications, and meditations as to how they should function in our common life.

Though a tiresome analogy, the concept of Anglicanism as being a “big tent” is not entirely worn out and can be useful in the proper setting. One can take shelter under the expansive covering inside the tent and feel at home. As Anglicans, we organize ourselves based on our reception of the prayer book, our understanding of ordination, our theological interpretation of the sacraments, our vestments, and so on and so forth. We treat the Articles as something by which we can organize once inside the tent and I believe this is where we get into trouble. We have expended and exerted such great energy in making sure that the tent is large and exhaustive, but we have done this to the detriment of making sure the tent is held up by sturdy posts and nailed down around the outside with stakes and markers.

If you will allow me to continue using the analogy here, my goal is to provide this significant blog series with the framework by which we can read the Articles together. This introductory post is not an attempt to settle the meaning of specific Articles once and for all, but rather to attempt to look through and beyond the varying camps of churchmanship in order to see the foundation underneath. Originally, I intended this essay to be a setting of the table for the other authors in the series but I now see that it is more of a fencing of the table (liturgical pun intended). At the end of the day, we may still disagree as to the importance of the Articles and what some of them may mean, but when we honestly read them together in their proper context, we are engaged in something that is building up the community of faith rather than tearing it down.

Context is everything. Many Anglicans get themselves into trouble when they begin ripping the Articles out of the historical context in which they were originally compiled and for which they were intentionally written. The same is true of biblical interpretation but we have no problem labeling such carelessness as “proof texting.” This ought to be applied universally when it comes to the Articles. Any interpretation of an individual article or the whole collection which does not pay attention to historical context is automatically starting from a place of deficiency and bias. The unique and precise historical situation which is the English Reformation, as seen through the lens of Cranmer’s liturgical revolution, the long-standing tradition of translating the Bible into English, and the need for the Elizabethan Settlement all provide the rich soil out of which our Articles grew.

We must treat the Articles as a contiguous collection, as a text which was written by a specific people, for a specific people, and during a specific historical, political, socio-economical, and theological context. Just as one cannot ignore Romans 9-11 while interpreting Paul’s letter to the church in Rome or neglect to pay adequate attention to the more “difficult” verses, passages, and books (has anyone read Job, Leviticus, or Ecclesiastes?!) of the Bible, so too must we take the Articles as a whole and not just the sum of its parts.

The language of the Articles can also provide an interpretive battle ground. We find ourselves caught up in asking questions such as, “But what does it mean when the Reformers used the word ‘transubstantiation?’” or making comments about “what they really meant to say was…” No text is without interpretation, but we find ourselves on faulty ground when we ignore the literal, grammatical meaning of the document in an attempt to “pay” it enough to make it say what we want it to say.

For those of us today who are worshipping in the Anglican tradition around the globe, the 39 Articles provide the boundaries within which we find ourselves existing ecclesially. The tent is held up by those truths which we cannot ignore, the commitments we have made as Anglican Christians for centuries. We are held up by Scripture, Prayer Book, Creed, historic episcopate (locally adapted), sacraments. There can be no argument here. The tent is staked to the ground (Cranmerian pun intended) by the Articles because together as one cohesive and comprehensive unit do they provide the boundaries and fencing we so desperately need.

What then do the Articles provide for us? With the understanding that they are neither comprehensive nor exhaustive, one can see that the Articles provide the rules for our own language game, the building blocks for our distinct way of doing theology, and the stakes which hold down the tent. Perhaps our attention would be better spent figuring out what it means to wrestle with the issues and questions of our present day along the same lines as the Reformers of the 16th century instead of arguing about what the Reformers actually meant as we seek to parse out Rome, Canterbury, Geneva, and Wittenberg.

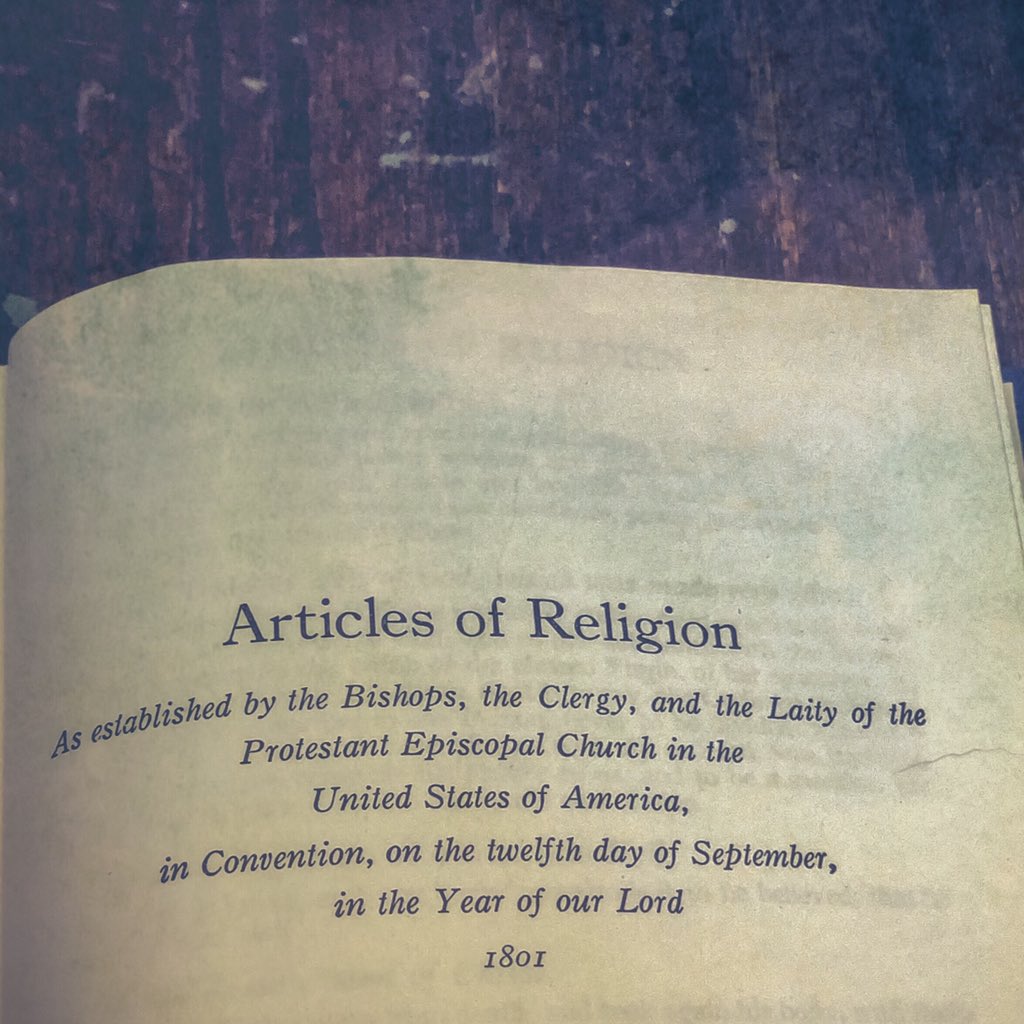

The 1979 Book of Common Prayer includes the Articles within the section “Historical Documents” sandwiched between the Athanasian Creed and Preface to the First BCP on one side and the Lambeth Quadrilateral on the other. Do we find this to be a coincidence? The Creed and Preface are foundational to our belief and the Quadrilateral is a measuring tool for ecumenical relationships…and the Articles float betwixt the two. That they are included in the BCP at all suggests they are important for our common life and worship; that they are included in the “Historical Documents” section implies that they are a historical hook upon which we can hang our hats; that they are next to the Quadrilateral could be seen as an attempt to use the Articles as a means of differentiating ourselves from other Christian traditions. Is this not in fact the very situation the Reformers were in? Were they not trying to differentiate the Church of England, the ecclesia Anglicana, from the Church of Rome and the reformations on the continent? You would be hard pressed to argue otherwise.

There is more, much more, to be said on many of these important issues but the Reformers have helped us by providing a standard against which we cannot nor should not seek to wander. The questions asked and answered in this blog series have a great deal to do with living and applying the Articles within a 21st century, North American Anglican context and exploring what they may mean for our common life together. Join us on this journey as we read together, setting aside biases of churchmanship and school theology, and allow yourself to ponder answer the pressing questions of today as read and examine through the guiding framework of the Articles.

The tent is as big and as expansive as ever, friends, but it is not limitless. We have boundaries, stakes if you will, which outline the tent as if saying, “You may go no further.” There is freedom within fences, as the adage goes, and plenty of room to run and play, but the markers are always and only meant to protect, guide, and ensure the passing along of tradition as we have received it. Do not cast the Articles aside as irrelevant because that is lazy; do not make them into more than they are because that is proof texting; do not continue the arguments over language and theological minutiae because that only isolates within the community. Let them be what they are: a theological response to distinct controversy and unique division within a historical context…and a model by which we can continue living as Anglican Christians in the world today.

Porter C. Taylor is a PhD student at the University of Aberdeen where he is writing his dissertation on liturgical theology. He is a priest in the Anglican Diocese of Pittsburgh and serves at Church of the Apostles, Kansas City as Theologian in Residence. Porter lives in Kansas with his wife, Rebecca, and their three sons. His work can be found on his website www.porterctaylor.com.

Very insightful