Editor’s Note: Another bonus post in our 39 Articles series, dealing with the ethics of oath-taking.

by Imai Thomas Welch

“Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?”

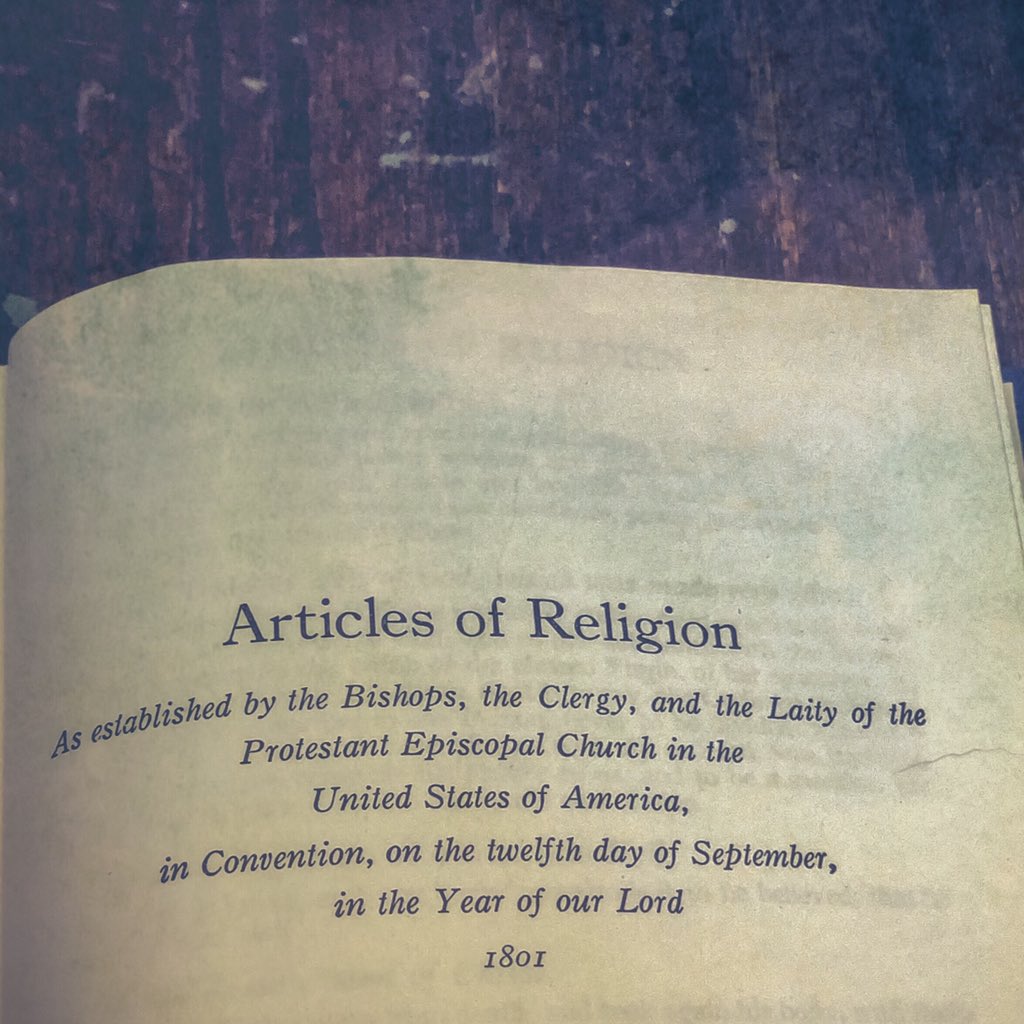

The last Article of the 39 Articles, “Of a Christian man’s Oath,” seems to be one of the more little-discussed Articles of the 39. Yet it is one of the Articles that deals with a very practical matter: is it acceptable to swear an oath, when asked (or required) to do so? The writers of the 39 Articles thought it certainly was acceptable. Here’s the official text of the Article from my Canadian Book of Common Prayer:

As we confess that vain and rash Swearing is forbidden Christian men by our Lord Jesus Christ, and James his Apostle, so we judge, that Christian Religion doth not prohibit, but that a man may swear when the Magistrate requireth, in a cause of faith and charity, so it be done according to the Prophet’s teaching, in justice, judgement, and truth.

(I should mention that I’m a Canadian living and practicing the Faith in Canada, born of British and British Caribbean parents, so I will be making references to Canadian and British laws and history at a few different points in this post).

So, what is an Oath and what is Swearing in this case? The Oxford Dictionary of Current English gives the following definitions:

Oath: A solemn promise to do something or that something is true.

Swear: Promise solemnly or on oath.

Once one has reached a certain point in their adult life, it is very likely they will have had to verbally swear an oath in one legal matter or another (and very possibly sign a written version of that oath!). This is no small matter. When you swear an oath, as the Oxford Dictionary definitions imply, you are promising that what you are saying or declaring in writing is true to the best of your knowledge. Knowingly giving a false statement under oath is a very serious criminal offense, has been for millennia, and is still punished accordingly. Nowadays, besides social condemnation and other punishments such as losing your professional licence or being defrocked, the false swearer (i.e.: a perjurer) can face significant prison time. Under the Criminal Code of Canada, perjury can be punished by up to 14 years in prison, which is the most severe non-life-imprisonment prison sentence available in Canadian law for a single criminal act.

The law has generally allowed for persons to swear an oath according to their own religious or spiritual customs for some time. British law has long made provision for this, in particular, with interesting applications in British Columbia over the years[i] However, it has only been quite recently that a non-theist Affirmation in lieu of an Oath has been considered generally acceptable on any real level. Although the American Constitution has allowed for Affirmation of the Presidential Oath since its writing, in the United Kingdom Members of Parliament have only been allowed to affirm in lieu of swearing an oath to enter Parliament starting in 1888. Even nowadays, as in the case of the American Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, affirming in lieu of swearing the oath can raise some eyebrows.

To give the necessary religious context behind Article 39, however, we must look to the Reformation. During the Reformation, the Anabaptists (from which developed groups such as the Amish, Mennonites, and Hutterites) argued that oaths were both unnecessary and inappropriate for a Christian. Quoting New Testament passages such as Matthew 5 and James 5, they argued that honesty should be presumed from any proper Christian, even if the Old Testament has numerous examples of the people of Israel swearing oaths.

While honesty should be expected from any person of faith, such thinking did not account for the reality of the Ecclesiastical Courts. At least in England, the Ecclesiastical Courts retained significant civil jurisdiction even after Henry VIII reined in their power during his reign. They held limited jurisdiction over wills until well into the Victorian era (1857, to be precise), and prior to the Victorian era, also acted as a sort of morality court for British citizenry. (They dealt with so many cases of questionable moral conduct that they earned the nickname of the “bawdy courts”!).

The administration of justice, then as now, presumed that the courts needed a guarantee of some sort that witnesses and other persons presenting themselves to the court would be honest. Oaths were, and remain, a standard way to confirm the intention of honest statements. So, how did one deal with the challenge posed by the Anabaptist arguments against oaths?

In the end, the challenge to oath-taking was theologically addressed in three ways, all of which are included in the Articles in one way or another. First, of course, there was the direct declaration that oaths were permissible, in Article 39. Second, the writers of the Articles directly addressed the issue of the Old Testament’s relevance to Christian living and its use in law in Article 7 (“Of the Old Testament”). Amongst the statements made in Article 7, the writers noted that while “the Old Testament is not contrary to the New” for theological purposes, it was still acceptable to make use of the Old Testament for other purposes:

“Although the Law given from God by Moses, as touching Ceremonies and Rites, do not bind Christian men, nor the Civil precepts thereof ought of necessity to be received in any commonwealth…”

Or put simply for our purposes, Old Testament justifications for legal matters are permissible, but also optional in nature. It was (and is) up to the government of the day to make the final call as to the Old Testament’s relevance to a legal matter. Hence, a government could continue the requirement of swearing oaths, as occurred in the Old Testament.

The third way of addressing the matter of oath-taking was by preaching. This use of preaching relates in a historical and indirect way in Article 35, “Of the Homilies”. As implied by the wording of Article 35, there was actually an earlier version of the Anglican Book of Homilies than the one discussed in the Article. This first version was issued in 1547 (the second version referred to was published the same year as the 39 Articles, in 1571). One of the sermon topics in that first book was “Against Swearing and Perjury.” The title is a bit of a misnomer, since the sermon directly addressed why and how oaths were permissible, and why they should be taken seriously.[ii] Although the sermon was ultimately deleted from the updated Book of Homilies, the writers of Article 39 may very well have had the sermon in mind when writing up the Article.

Long and short, Oaths, for a Christian, are as much a religious matter as a civil matter.

As a final side note: the 39 Articles are a fascinating element of Anglican theology. Article 39, in some ways, reflects some important elements of the overall thought behind the Articles and their implications for the Anglican theological tradition. The Articles might be regarded as “Historical Documents” in much of the Anglican Communion, but that certainly does not mean they are no longer relevant!

First, the Articles deal both with more strictly “spiritual” matters and more “practical” matters. Article 39 would qualify as one of the more “practical” Articles. Anglican theology has never really been inclined to ignore the practical matters of life in this world. Second, if you look carefully at how the Articles were ultimately numbered and formatted, there appears to have been a specific choice of the authors to first deal with spiritual matters in the first Articles and then gradually migrate to more “practical” matters in the later Articles. This is in addition to the various retorts, rebuttals, and replies being made in the Articles to both the Roman Catholics and various Protestant theologians in the thick of the Reformation.

Third, the Articles are interconnected. As I noted, Article 39 has connections to Article 7 and Article 35. I’m sure many readers of this post, if they looked carefully, could find other linkages between the various Articles.

The authors of the Articles understood, as the Christian Church has understood from the times of the Early Fathers, that religious faith has real-life implications and real-life consequences. And different elements of the Faith are not siloed, but rather become interconnected because those different elements of the Faith have implications on a given matter of regular Christian living. Or, as I sometimes like to say, doxios and praxis inform one another!

Imai Thomas Welch is an urban planner in Edmonton, Canada.

[i] A fascinating discussion of what sorts of oaths have been allowed in British Columbian courts over the years can be found at http://www.provincialcourt.bc.ca/enews/enews-27-11-2018.

[ii] The sermon can be found at https://forums.anglican.net/threads/homily-1-7-against-swearing-and-perjury.1971/.