by the Rev. Dr. Daniel W. McClain

- There is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body, parts, or passions; of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness; the Maker, and Preserver of all things both visible and invisible. And in unity of this Godhead there be three Persons, of one substance, power, and eternity; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Perhaps you’ve heard that old rectors’ gag: “It’s the curate’s/associate’s/seminarian’s job to preach Trinity Sunday.” As a joke, I suppose it seems harmless. Yet, I wonder if it reveals more than we’d like to admit about the contemporary Anglican disposition toward Trinitarian theological thinking. Sure, many of us (Anglican clergy) can rattle off dusty bits of theological trivia from seminary. But, take for instance, a common revision to the opening acclamation of our Eucharist—we’re tongue-tied when it comes to explaining why the opening acclamation in the liturgy drops the names “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,” for “Creator, Sustainer, and Redeemer.” And, while we’re fluent in respecting “the dignity of every human being,” we’re unclear about why we recite the Apostle’s Creed as the first part of our baptismal covenant. It’s not that we intentionally are trying to be modalists. It’s just that for most clergy and laity, certain political pressures make the “Creator, Sustainer, Redeemer” revision a quick and easy solution to an apparent problem. Indeed, most Episcopalians are probably just as happy to accept what seems to be a rather handy description of God via God’s activities, regardless of the fact that it does so at the expense of the three triune persons. It saves face for those who either dislike theological reflection or find the doctrine of the Trinity counter-intuitive, or embarrassing.

I mean, why do we even have a day set aside to celebrate a doctrine anyway?

But the problem goes deeper than expecting any rector or layperson to give a coherent account of the Trinity. We like people and the creation, a lot. And so we understandably cling to the dignity of every person and seek to use creation’s resources rightly. We don’t appear to understand, however, how that human dignity and the dignity and goodness of all creation are anchored in the eternal and undivided life of the Trinity, the “maker and preserver of all things visible and invisible,” the one in whose image every person is made. Consequently, our theological rationale for why we affirm the goodness of creation and human dignity is thin.

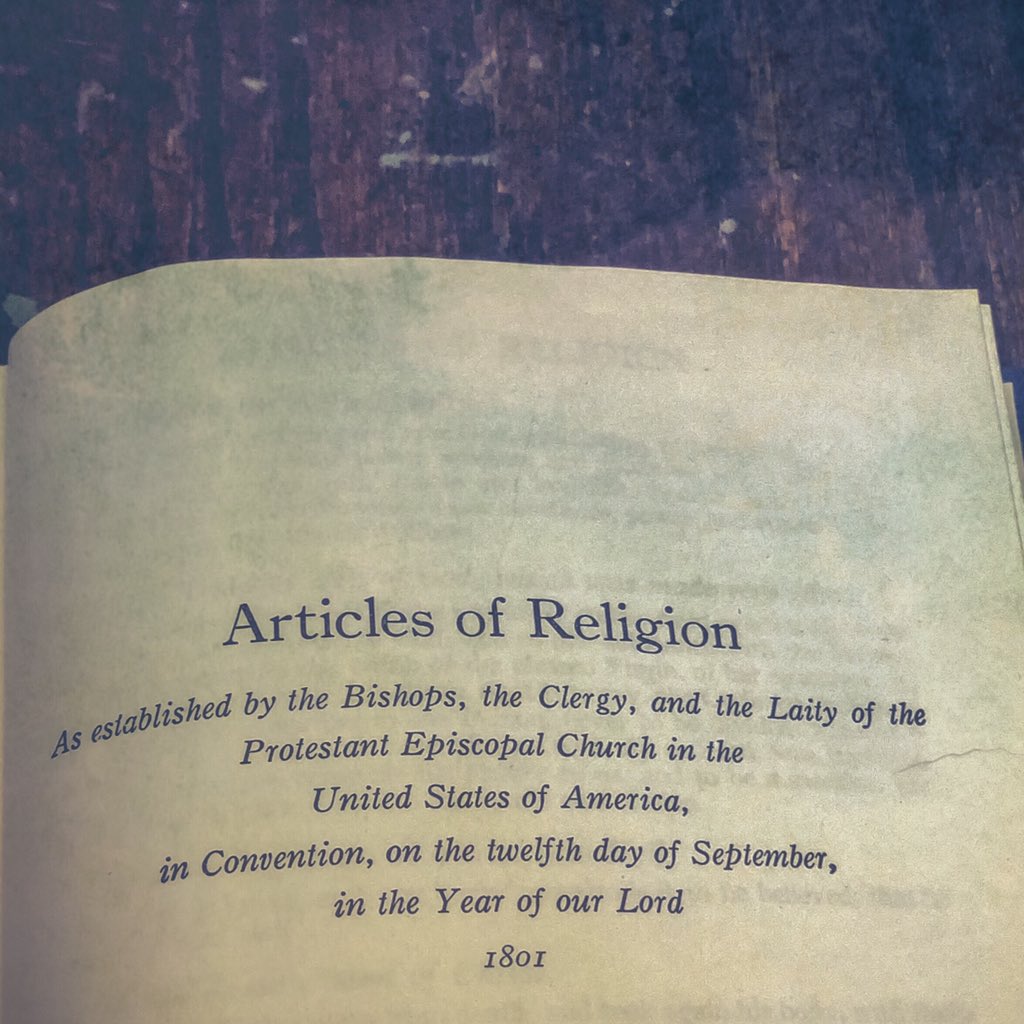

And that’s unfortunate, not least because we have ample resources for theological reflection and justification. The Trinity is the foundation of the Anglican rule of life, which encompasses how we should live, pray, and think. The Bishops of the Church of England, and then again of the Episcopal Church, made this clear when they placed teaching about the Trinity as the first of the 39 Articles, signaling the primacy of the doctrine of the Trinity for all doctrine that follows. This is not simply a matter of emphasis. Rather, Trinitarian teaching informs our beliefs as well as our social imaginary, that is, the way we think about being followers of Christ in the world. And that is all-encompassing. A Trinitarian social-imaginary includes our social relations, our patterns of education and habits of self-reflection, and above all our relationship to God, expressed primarily through prayer and liturgy.

For example, the Trinity informs Eucharistic celebration in the Book of Common Prayer: we acclaim the Trinity; we address the prayer of the Eucharist to the Father, through the Son, in the Unity of the Holy Spirit; and we receive the blessing of the Trinity as the consummation of the Eucharist. And, of course, we recite the Nicene Creed before the Eucharistic prayer begins. Likewise, the Apostles’ confession of the Trinity structures the oath of the baptismal covenant. Our liturgy is rife with the Trinity.

This teaching not only universal; it is alive and dynamic. As E. L. Mascall once said about confessions of the Trinity, “they have unexpected implications in previously unexplored areas of human concern, they come to new life in bypaths where to all appearance they seemed to have reached a dead end, and from time to time they link on an invigorating way to new advances in the secular sciences and in philosophy” (Mascall, The Triune God: an Ecumenical Study, 8). And as much as this dynamic leads to discoveries, it also leads to limitations, especially in the language and concepts we use and don’t use for the Trinity. Theologians typically employ analogy to overcome these limitations. For instance, God is considered supreme oneness and unity, and yet we discover how excellent and superlative that unity is in the perfect love of the three persons for each other. Likewise, we affirm the complete deity of all three persons against the heresy of modalism, and yet we resist its counterpart, tri-theism. Here, Augustine developed the notion of subsistent relations, or one being constituted relationally, in order to preserve the Unity of the Godhead and the integrity of each Triune Person.

This relationship of unifying and self-giving love of these three persons can be described according to any number of analogies, such as memory, understanding, and love, also popularized by Augustine. And we employ the analogy of the gift to reflect the relationship of the members to each other and to us. Hence, God the Father is the perfectly abundant source of all good gifts, the preeminent of which is the gift of the Holy Spirit. And yet, God is also that Gift wholly-given. Perhaps we see a glimmer of such persons constituted eternally and relationally in our own finite social relations, but our language and experiences struggle to adequately reflect the excessive perfection of the divine, triune life, however much we must speak and, indeed, are called to speak truthfully about God.

Finally, we should remember that no doctrine or dogma of the faith is an end unto itself, but always another tool or resource for shaping our love of God, for bringing us to the threshold over which we enter into our homeland, which is eternal life and joy with God. This is why our affirmation of the Trinity, perhaps best expressed in the Creeds, is meant to be studied, then prayed, and then finally left behind in the summit of perfectly loving union with God. But before we can leave behind the doctrine itself, as Austin Farrer once reminded us, we must meditate continuously upon it. “For no spiritual truth, however fundamental, is once and for all acquired like gold locked in a safe. We think it is there… But when we look for it, either it has vanished or it is no longer gold. It has turned as dull and soft as lead, and must be transmuted back to hold by the alchemy of living meditation” (Farrer, Lord I Believe, 16).

Whether we are layfolk or clergy, is it not a privilege, indeed, an exalted privilege to participate in the Spirit’s work of shaping the prayer, meditation, and imagination of the Church? Why would we shy from that privilege, even especially on a day dedicated to the three persons of the Trinity? How better to foster the meditation of the Trinity, what better way to incite love for our God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, than to preach about God regularly, to bring the good news, however mysterious, about the perfect unity and love of our God, who calls us to participate and share in the love through adoption in Christ?

The Rev. Dr. Daniel Wade McClain is an Episcopal priest, an adjunct professor at the General Theological Seminary, and the Episcopal Chaplain at the College of William and Mary.