There is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body, parts, or passions; of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness; the Maker, and Preserver of all things both visible and invisible. And in the unity of this Godhead there be three Persons, of one substance, power, and eternity; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

by Wesley Hill

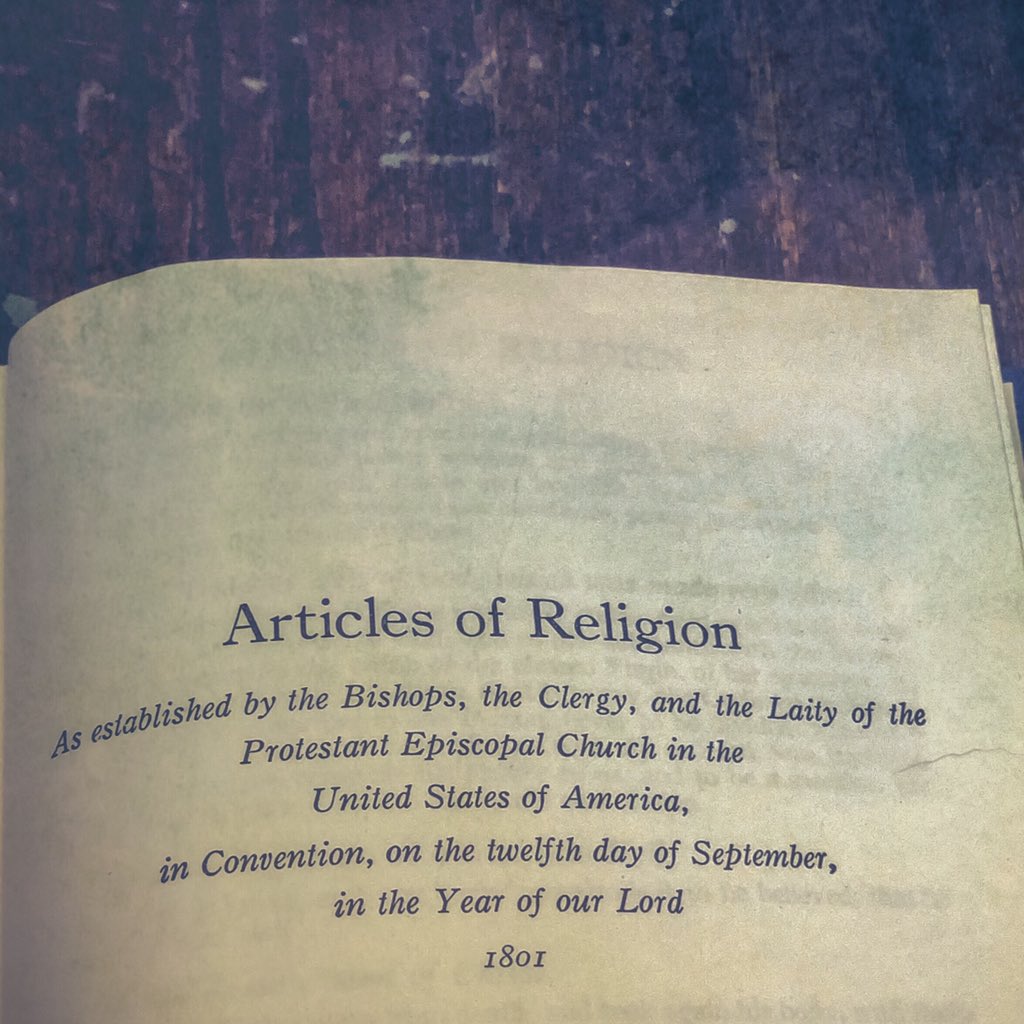

The Thirty-Nine Articles open with a vision of a God who is incomprehensibly other. In language borrowed from the Hebrew Bible (or, as Christians know it, the Old Testament), Article I first speaks of God as utterly unique: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord” (Deuteronomy 6:4, RSV). Article I presupposes the Jewish conviction that the God who is revealed in the events of Abraham and his descendants’ election and redemption is fundamentally unlike the gods of other nations. The Gentiles may have their mute and dumb idols, but Israel’s God is alive — free to speak and surprise (Jeremiah 10:10; Wisdom 12:17; Sirach 18:1) — and, just so, the true God who exposes would-be rivals as ultimately shadowy nonbeings.

But when Article I says that God is singular, living, and true, it is not simply renouncing polytheism. More fundamentally, it is pointing to God’s incomparability, God’s transcendence. Nothing in the world of created goods is like God. God is sui generis: without peers or rivals. If God compares Godself to created realities — such as a rock (Psalm 18:2) or a shepherd (Psalm 80:1) — it is not because those terms tell us exactly what God is like, as though God could be apprehended by frail human language. God makes use of metaphor and analogy to communicate with us, but we must never think that because we know what a rock or a shepherd (or a father or a warrior or any of the other images God uses) is in our terms, that God is exactly the same. As theologian Katherine Sonderegger reminds us, “[T]here can be no affirmation of God that is not controlled by the radical negation of form, image, and likeness.” We can know God truly because of God’s self-communication, but we should never think that we thereby comprehend God fully or escape the need to qualify all our speech with “but also unlike….”

And that brings us to the Article’s next moment. After describing God as one, living, true, and everlasting, Article I says that God exists “without body, parts, or passions.” The Article is not shy about speaking positively of God’s eternity, power, wisdom, and goodness, but it is at the same time anxious to underscore how God exceeds any idea we have of what God’s power, wisdom, and goodness amount to. Upon hearing God described as a king or a provider, we may find ourselves picturing the mercurial and passionate rulers in our geopolitical scene, projecting traits from the creaturely realm onto God as if God were a king like the ones we know — only bigger and better. Well before Enlightenment thinkers taught us to be suspicious of such “onto-theology,” the “negative,” apophatic emphasis in the Christian tradition — represented here in Article I’s “without…” clause — was designed to safeguard the doctrine of God from the encroachment of idolatrous divine misattribution. Saying that God exists without a body, without composition, and as impervious to the whims of passion is to say that, when we characterize God as alive, eternal, powerful, wise, and good, we should always remember that God is so in a way fundamentally, ineffably different from us us. “[T]he Glory of Israel… is not a mortal” (1 Samuel 15:29, NRSV). We can and should say that God is all that God is revealed to be, but we should always be prepared to turn back on the language we use in prayer and theology and be aware of the ways it fails to package or control or exhaust the mystery of who God is.

Article I goes on to describe God’s relation to what is not God: God is “the Maker and Preserver of all things both visible and invisible.” According to this affirmation, everything material — and every thing immaterial, which is to say, creatures that take up no space in our cosmos, like angels — owes its existence to God. God, in other words, is the reason anything exists at all. It’s important to linger on this point because it is today among the most misunderstood affirmations found in the Thirty-Nine Articles (and in Christian theology more generally). The Christian (and Jewish) doctrine of creation is not that God is to be found somewhere along the timeline of the universe’s unfolding, such as at the Big Bang and/or at the hinge points of, say, the emergence of new life forms or the appearance of human language. Rather, to call God “maker” is to invoke God as the underlying and intimate sustainer of the entire fabric of the universe(s). God is not a bigger, stronger version of other finite causes; God is whatever — or, better, Whomever — holds the entirety of life as we know it in being. So, contrary to the likes of Richard Dawkins and Neil deGrasse Tyson, it is no defeater for belief in the God to whom Article I refers if scientific observation needs no recourse to an unexplained intervention in order to account for the workings of nature. Christians can simply nod their heads in agreement whenever Dawkins and his tribe reject belief in an old man in the sky who occasionally intervenes in the world’s causal chains. We don’t believe in a creator like that either because we don’t think that really counts as “creation” to begin with. For God to be the “Maker and Preserver of all things” is a different thing entirely; God is the unseen One whose love and ongoing generosity are the reasons for there being a world at all.

With those affirmations in place, Article I begins to speak of God as triune. There is, it says, a “unity” in the Godhead. In the metaphysical language that the Church Fathers took over from Hellenistic philosophy and baptized, there is one divine “substance” or “essence” (ousia in Greek). While not explicitly found in Scripture, this language is meant both to translate for a non-Jewish audience as well as to safeguard the conviction that the apostles found in Israel’s Scriptures — namely, God’s oneness that we’ve been discussing above. Nonetheless, what the apostles witnessed in the events of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, and through their experience of his Spirit on the day of Pentecost and beyond (Acts 2:1-4), forced them to understand God’s oneness differently than they had before.

Jesus had affirmed his own faith in the oneness and uniqueness of the God of Israel, in part by quoting the book of Deuteronomy’s “Hear, O Israel…” (Mark 12:29). Jesus embodied an unprecedented intimacy with God, preferring above all other designations the title “Father” for God. Certainly there was precedence for the use of this title in Israel’s Scriptures. The Jewish people understood themselves to be, collectively, God’s adopted child (Exodus 4:23), and Israel called upon God thus: “you, O Lord, are our father; our Redeemer from of old is your name” (Isaiah 63:16). But Jesus went further. Not only did he borrow one of his people’s favorite designations for God; he also claimed that his intimacy with the One he called Father far surpassed anything known before. “All things have been handed over to me by my Father, and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” (Matthew 11:27). More succinctly: “The Father and I are one” (John 10:30).

To many of his first hearers and followers, this presented a seemingly insoluble dilemma. Either God had a Son, Jesus, who was as divine as God was, in which case Israel’s monotheism was fatally compromised, or else Jesus wasn’t equal to God, in which case his grandiose claims to be able to forgive sins and remake the world were nothing more than the pipe dream of an idealistic but ultimately ineffectual prophet. And the situation with Jesus’ “Spirit,” his unbodily personal power (as Dallas Willard nicely expresses it), was similar. The apostles throughout the New Testament seem to vacillate between saying the Spirit is different from God the Father and God’s Son Jesus and saying that the Spirit says and does things that only God can do (for instance, John 6:63: “The Spirit gives life” [NIV]).

The solution to this challenge that the church eventually found — a solution that took centuries of theological wrangling and writing to appear in the form that we now know as the Nicene (or Niceno-Constantinopolitan) Creed of 381 CE — was to say that, while truly human, Jesus was at the same time God; and that the Spirit, while distinct from the Father and the Son, was at the same time fully God — but that there remained only one God.

The church continued to feel the constraint of the Old Testament and to confess its basic affirmation: God is one. But God’s oneness was now seen to be irreducibly — and mysteriously — threefold. The sonship of Jesus, like human sonship, meant that God the Father gave the Son his being (“For just as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself” [John 5:26]); but unlike the case with human fathers and sons, the divine Son’s relation to the Father did not have a temporal beginning point. There was, as the early church’s anti-Arian slogan goes, never a time when the Son was not. Thus the creed, on which Article I depends, says that the Son is “eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made” (emphasis added). And the Spirit, likewise, depends on the Father and the Son for his life — the Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son” — in such a way that the Spirit thereby possesses identically the same divine essence as the Father and the Son: “With the Father and the Son he is worshiped and glorified,” as the creed has it. And it is this set of convictions and claims that Article I aims to encapsulate.

It is worth asking, at this point, the question that every preacher asks when Trinity Sunday rolls around: So what? Or, with less bite: All this is well and good, but how does it intersect with lived Christian experience?

The doctrine of the Trinity, with which Article I closes, is meant, among other things, to offer assurance to wavering consciences. If we ever wonder whether the grace and new beginning we have experienced through Jesus’s love and the Spirit’s presence among us is merely the momentary kindness of an otherwise unpredictable God, Trinitarian theology says, “No, this is how God fundamentally is — all the way back into eternity, and all the way into the coming kingdom.”

The late Reformed theologian T. F. Torrance tells a story of when he worked as a chaplain during World War II. On a battlefield in Italy, a dying soldier grasped Torrance’s arm and said, “Padre, is God really like Jesus?” Torrance spent the rest of his theological career spelling out the answer he gave to the soldier that day: Yes.

God is not one thing in himself and another thing in Jesus Christ—what God is toward us in Jesus he is inherently and eternally in himself. This is the fiducial significance of the central clause in the Nicene Creed, that there is a oneness in Being and agency between Jesus Christ the incarnate Son and God the Father. What God is in eternity, Jesus Christ is in space and time, and what Jesus Christ is in space and time, God is in his eternity. There is an unbroken relation of Being and Action between the Son and the Father, and in Jesus Christ that relation has been embodied in our human existence once and for all. There is thus no God behind the back of Jesus Christ, but only this God whose face we see in the face of the Lord Jesus. There is no deus absconditus, no dark inscrutable God, no arbitrary Deity of whom we can know nothing but before whom we can only tremble as our guilty conscience paints harsh streaks upon his face. No, there are no dark spots in God of which we need to be afraid; there is nothing in God for which Jesus Christ does not go bail in virtue of the perfect oneness in being and nature between God and himself. There is only the one God who has revealed himself in Jesus Christ in such a way that there is perfect consistency and fidelity between what he reveals of the Father and what the Father is in his unchangeable reality. The constancy of God in time and eternity has to do with the fact that God really is like Jesus, for there is no other God than he who became man in Jesus and he whom God affirms himself to be and always will be in Jesus.

(Thomas F. Torrance, The Christian Doctrine of God, pp. 243-244)

That is where the Thirty-Nine Articles begin: with a God whose infinite power, wisdom, and goodness are turned toward us in love.

Wesley Hill is associate professor of New Testament at Trinity School for Ministry, Ambridge, Pennsylvania. He is the author of Paul and the Trinity (Eerdmans, 2015).His book on the Lord’s Prayer is forthcoming in 2019.