The Second Book of Homilies, the several titles whereof we have joined under this Article, doth contain a godly and wholesome Doctrine, and necessary for these times, as doth the former Book of Homilies, which were set forth in the time of Edward the Sixth; and therefore we judge them to be read in Churches by the Ministers, diligently and distinctly, that they may be understanded of the people.

by Dr. Francis Young

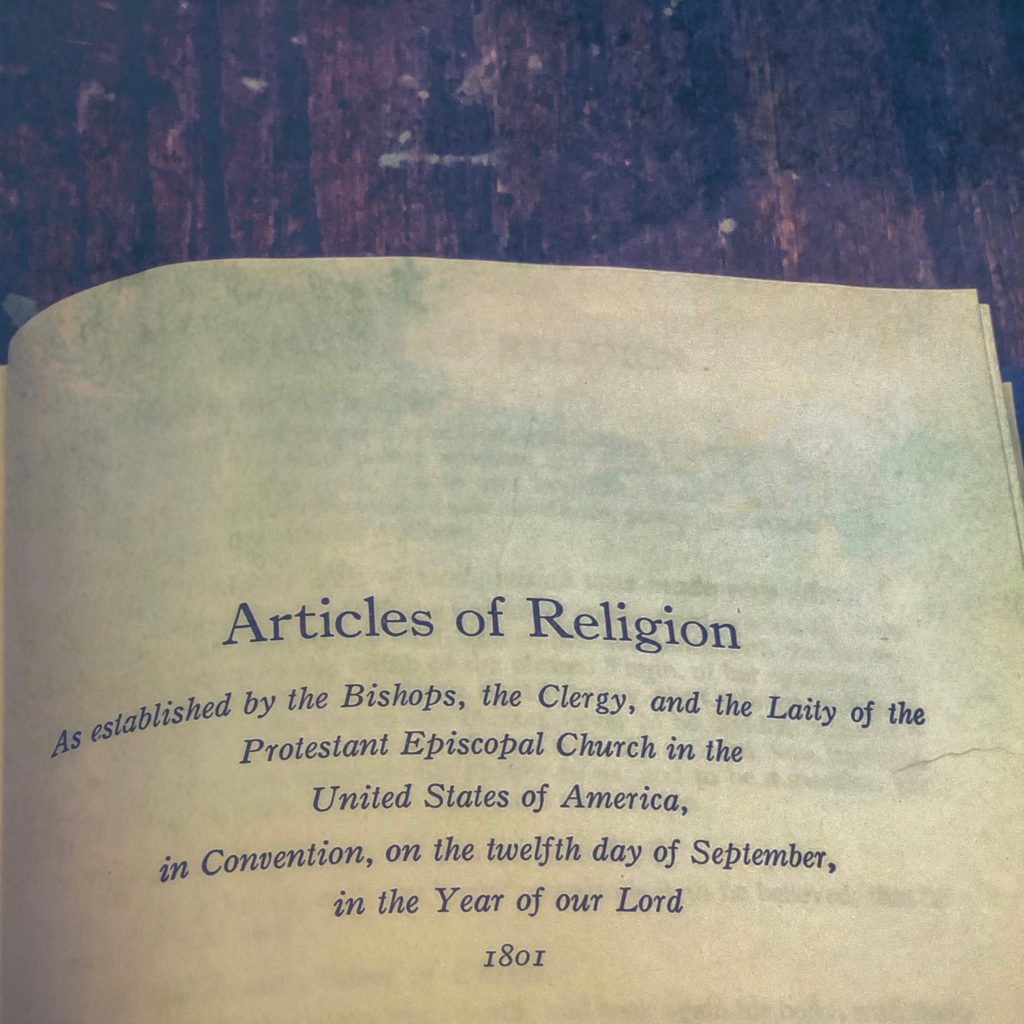

Of those Articles of Religion that are most at risk of being accused of obsolescence, Article 35 on the Books of Homilies is surely a foremost candidate. The Article enjoins ministers to read the sermons from the Second Book of Homilies, published in its final form in 1571 and largely authored by the great Elizabethan Anglican apologist John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury (1522–71). The Homilies are, in theory, the only book that stands alongside the Scriptures and the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer as a normative articulation of Anglican doctrine, yet the Homilies are so little known today that many Anglicans will never have heard of them. Indeed, a modern edition of the First and Second Books of Homilies was not even available until 2006.

Before considering the historical context of the Homilies, it is worth noting the ambiguous language of Article 35, which is phrased in such a way that it does not necessarily make the reading of the Homilies compulsory. The Article endorses the Homilies, which ‘contain a godly and wholesome Doctrine, and necessary for these times’; yet the Article does not ‘command’, but rather ‘judge[s] them to be read in Churches’. While the Article is explicit in its endorsement of Bishop Jewel’s Second Book of Homilies (even listing every one of the Homilies by name), its endorsement of the First Book of Homilies (1547), largely authored by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in the reign of Edward VI, is less clear. The Article compares the Second Book of Homilies with the First Book, which was necessary in the time of Edward VI just as the Second Book is necessary in the reign of Elizabeth, but there is no clear statement that the First Book remained relevant or appropriate after the Elizabethan Settlement. Is the Article saying that Jewel’s Homilies are relevant to the present as Cranmer’s were to the past, or that Jewel’s Homilies ought to be added to a deposit of faith already represented by Cranmer’s Homilies? As it stands, Article 35 cannot be read definitively as an endorsement of both Books of Homilies, but only as an explicit endorsement of the Second Book of Homilies.

The Books of Homilies served three main purposes. Firstly, the sermons within them articulated Anglican doctrine, especially Anglican positions in ecclesiology and soteriology, in much more detail than The Book of Common Prayer and the Thirty-Nine Articles. Secondly, the sermons served as an accessible theological resource that underpinned the preaching of the clergy at a time when little distinctively Anglican theological writing yet existed, and the writings of the Continental Reformers were both hard to obtain and written in Latin. And thirdly, the Homilies could be read in place of a sermon by clergy (and, in some parishes, lay readers) who did not hold a licence to preach. It was this third purpose of the Homilies that was the most important, because licences to preach were strictly controlled by the Elizabethan bishops and issued sparingly. Some bishops regarded preaching as a specialist ministry, which should be confined to university-educated clergy or even doctors of divinity holding senior positions within the diocese, such as the cathedral clergy. At best, preaching licences were confined to incumbents in priest’s orders (bearing in mind that, before 1661, not all incumbents were in priest’s orders); the curates, perpetual curates and chaplains who were often responsible for the day-to-day running of the parish church rarely held a licence to preach.

The result of this was that readings from the Books of Homilies would have been a weekly experience for a large proportion of Elizabethan parishioners – a fact that enraged Puritans, who frequently railed against the bishops for limiting preaching licences, and against ‘non-preaching parsons’ for declining to preach anyway, with or without a licence. The Books of Homilies were thus a flashpoint in the conflict between Puritans and more willing conformists that simmered within the Church of England between the 1570s and the 1640s and eventually tore it apart. The role of the Homilies as sermon-substitutes is also a key reason why they became largely obsolete from the later seventeenth century onwards, as bishops became less cautious in their licensing of preachers. With the advent of toleration for nonconformists after the Revolution of 1688, the bishops became less concerned about controlling the preaching of Anglican clergy and more focussed on the preaching of Anglican orthodoxy in the first place. The Homilies faded into the background, a theological mainstay of an earlier age of universally-enforced religious conformity.

In contrast to the First Book of Homilies, which focussed on issues of systematic theology that characteristically preoccupied the Reformation theologians of the sixteenth century (Scripture, justification and the relationship between faith and works), the themes of the 21 sermons of the Second Book of Homilies are more practical. Homilies 1 and 2 address the importance of maintaining and correctly using the church building; Homilies 4–6 and 20–21 deal with moral conduct; Homilies 7–9 are about prayer. Homilies 12–14 and 17 are seasonally specific to Christmas, Passiontide, Easter and Rogationtide. The remaining Homilies tackle almsgiving (Homily 11), worthy reception of the Sacrament (Homily 15), the gifts of the Holy Spirit (Homily 16) and marriage (Homily 18). The Second Book of Homilies makes up for the potential shortcomings of the highly doctrinal First Book by recognising the importance of the material environment of the worshipper, the practicalities of worship, the seasonal life of the church, and the role of the church in moral exhortation and the policing of mores.

What, then, should we make of the continuing presence of an Article of Religion enjoining the use of the Book of Homilies? By contemporary homiletic standards, the Elizabethan homilies are surely unusable. Some are extremely lengthy (such as the notorious Homily 2, ‘Against Peril of Idolatry’) and the frequent appeals to the authority of the Church Fathers would sound strange in most modern sermons. Furthermore, the importance of the lectionary in the contemporary Anglican church makes it difficult to see where some of the themes of the Homilies would fit into the liturgical year. In some cases, the language used against other Christians, especially Roman Catholics, is inappropriate to the modern world – not to mention the difficulty that a contemporary congregation would experience in accessing early modern English.

No-one, therefore, would (or should) consider using the Books of Homilies for one of their original purposes – namely, reading them out in place of a sermon to the congregation. However, as we have seen, acting as substitute sermons was only one of the original purposes of the Homilies. The Homilies were also a compendium of Anglican doctrine and a theological resource for clergy writing sermons. In these two respects the Homilies remain as important as they ever were. They present the theology of the Church of England as it existed at a point when the clergy of the Established Church clearly understood themselves as part of the nascent Reformed tradition, but with distinctively English emphases and approaches in both doctrine and practice. Furthermore, the Homilies are a valuable reminder of the significance that not only Scripture, but also the Fathers of the Church, held for early Anglicans. Unlike other famous Anglican works such as John Jewel’s Apology for the Church of England and Richard Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, the Homilies were not written as polemic for a learned academic audience, but rather for the common people: the man or woman in the pew. While the Homilies expected a rather longer attention span than we might find in a contemporary congregation, they cannot be written off as nothing more than excessively complex theological articulations thrust in the ears of ordinary folk, because the concerns they address are down-to-earth, pressing, and real.

The existence of the Homilies may trouble some Anglicans who cleave to the position that Anglican theology is defined solely by liturgy. This was not the intention of Cranmer and Jewel, who wanted to flesh out Anglican theology in as much detail as possible. On the other hand, the Homilies resemble the Articles in their adoption of nuanced theological positions and their continual insistence, especially in Jewel’s Second Book, on theological restraint (‘moderation’ is a somewhat misleading word to use in a sixteenth-century context of vehemently held religious views on all sides). The Homilies are simultaneously uncompromising and measured in tone; theologically comprehensive, yet straightforward; learned, yet practical (especially in the Second Book).

What can Anglicans do to reclaim and rediscover the Homilies? Editions of the Books of Homilies are now widely available, including a critical edition by Gerald Bray that shows the influence of the Homilies of 1547 on a set of Catholic homilies authored by Bishop Edmund Bonner in 1555 during Mary I’s reign, and the subsequent influence of those Catholic homilies on the Second Book of Homilies. What is needed next, perhaps, is an edition of the Homilies in modern English that will be accessible to the average contemporary parishioner – so that the Homilies can regain their position alongside The Book of Common Prayer as normative articulations of traditional Anglican theology and practice, a rich resource for the Anglican Communion that embodies the roots of Anglican faith.

Francis Young is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Reader in the Church of England. He is the author of 12 books including Inferior Office? A History of Deacons in the Church of England (2015) and A History of Anglican Exorcism (2018). He blogs at https://drfrancisyoung.com