“The Son, which is the Word of the Father, begotten from everlasting of the Father, the very and eternal God, and of one substance with the Father, took Man’s nature in the womb of the blessed Virgin, of her substance: so that two whole and perfect Natures, that is to say, the Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one Person, never to be divided, whereof is one Christ, very God, and very Man; who truly suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for actual sins of men.”

by Brendan Case

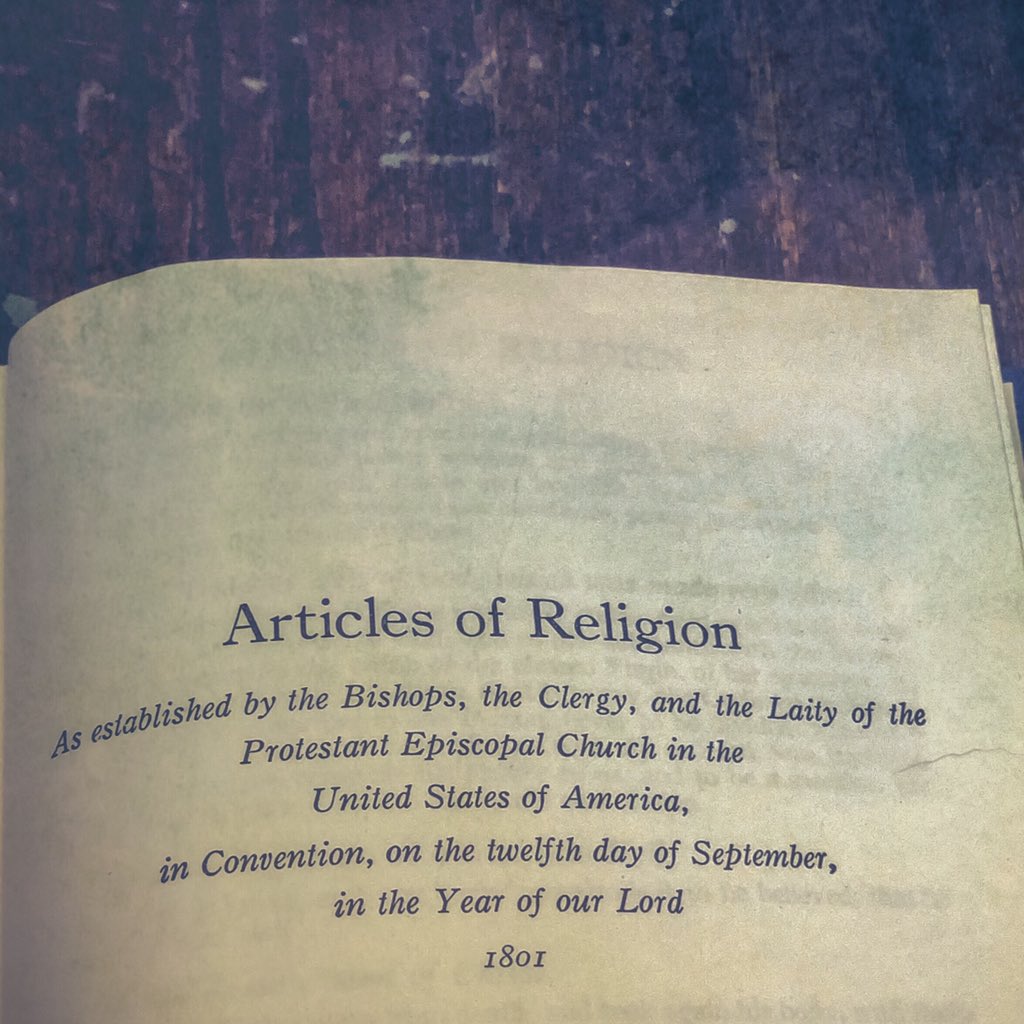

The first of the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (1571) summarized the church’s historic affirmation that there is one God, the creator of all that is not he, who nonetheless subsists eternally in three “persons,” the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The second article focuses particular attention on the divinity and assumed humanity of that Son. This article, like the Lutheran Confessions which were its parents (see below), summarizes and endorses central teachings from the Councils of Constantinople (381) and Chalcedon (451), thus demonstrating its drafters’ commitment to catholicity and tradition, while also obliquely criticizing some Anabaptists’ denials of the Trinity and the Incarnation, as well as the Roman Catholic account of the Mass as a “sacrifice.”

An overview of the Articles’ background and provenance can be found elsewhere in this series, but it’s important for our purposes to keep in view that the second of the Thirty-Nine Articles, like many of the others, is largely drawn from prior Lutheran Confessions, notably the Augsburg (or Augustana, 1530), and the Württemberg (1552).These and other texts from the Continental Reformation exercised a profound influence in England, particularly on Cranmer, the principal author of both the draft Thirteen Articles (1538?), and the Edwardian Forty-Two Articles (1552), which were finally revised by Matthew Parker and others into the Thirty-Nine Articles which have largely endured to the present. (For the above and more, cf. Charles Hardwick, History of the Articles of Religion (1851), p. 21-138.)

Article II opens with a summary of the Son’s divinity and Incarnation (“the Son…her substance”), taken largely taken from the third article of the Augustana, with a substantial insertion from the second article of the Württemberg Confession (“we believe and confess the Son of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, eternally begotten from his Father, true and eternal God, consubstantial with his Father”). Nonetheless, it also neatly summarizes the second article of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed regarding Christ’s eternal deity and Incarnation in time.

The Council of Constantinople (381) settled a decades’-long theological struggle sparked in Alexandria in 321, when a priest named Arius (250-336) took a long tradition of subordinating the Son to the Father to new extremes, with his teaching that “there was a time when [the Son] was not.” The emperor Constantine himself ultimately intervened in the ensuing debate, calling a council at Nicaea (325) that excommunicated Arius, anathematizing anyone who denied the Son’s eternal generation, and maintaining that Father and Son were “of the same nature,” “homoöusios” in Greek, quickly rendered into Latin as “consubstantialis,” which reappears in our Article.

In the near term, Nicaea settled little, however, as many balked at the extra-biblical provenance and apparently modalist implications of “homoöusios.” Opposition to Nicaea was fractured and fractious: some proposed to describe the Son as only “of a similar nature” (homoiousios) to the Father; some to dispense with “substance” talk altogether, in favor of simply affirming that the Son is “like” the Father (the “Homoians”); some to describe the Son as “of a different substance” (heteroöusios) than the Father.

Defenders of Nicaea – in the early stages, particularly Athanasius of Alexandria (ca. 296-373), and then later the Cappadocian trio of Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nyssa – insisted upon the homoöusion as the best gloss for passages such as John 1:1-3 (alluded to in the opening of Article II), in which it is the Word, who was “with God” and who “was God,” through whom all things were made (cf. also 1 Cor. 8:6, Heb. 1:2). After a sequence of emperors who favored one or another of the anti-Nicene positions, the pro-Nicene faction found decisive support from the newly-appointed Theodosius (347-395), who convened a second council at Constantinople (381), presided over by Nazianzen, which ratified and expanded the Trinitarian theology of Nicaea.

After the fifth century, increasingly strict ecclesiastical and legal sanctions against heresy left little room for continuing public debate over the doctrine of the Trinity. That changed with the Reformation, however, as the shifting and fracturing landscape of church and state surfaced dissent, not only regarding papal authority or the nature of the sacraments, but also, if much more marginally, regarding the Trinity and the Incarnation itself.

This dissent sprung up from the earliest days of the Reformation among the diverse range of groups lumped together as “Anabaptists.” There were those who denied the Trinity, such as Michael Servetus (1509-1553), famously burned for heresy in Calvin’s Geneva, or the slightly later Faustus Socinus (1539-1604). And there were others who revived the ancient “Docetism” of Valentinus (ca. 100-160), which denied that the Son was actually conceived by Mary. These included the Kentish Joan of Bocher, who, according to Hugh Latimer, said that “our Saviour was not very Man, and had not received flesh of His mother Mary…Her opinion was this. The Son of God, said she, penetrated through her, as through a glass, taking no substance of her” (quoted in Boultbee, A Commentary on the Articles of Religion, 15-16). The revival of this anti-Incarnational teaching doubtless accounts for the pointed insistence in Article II on Christ’s conception, not only (as in the Augustana) “in the womb of the Virgin Mary,” but indeed “from her substance.”

Having affirmed the fact of the Incarnation, Article II proceeds to explore its structure (“so that…very man”), as a union of the divine and a human nature in the single person of the Son. Though still following the Augustana closely, the Article also echoes the “Definition” of the Council of Chalcedon (451), at the close of “the Christological Controversy,” which was in fact a further stage in the debate launched by Arius about whether and how the transcendent God might appear, not merely among, but even as one of his creatures.

Where Arius had sought to protect God from contamination by the Incarnation by attributing it to an inferior deity, Nestorius (386-450), an enthusiastic Nicene Trinitarian, sought to relocate Arius’s barrier between God and humanity within the person of the God-man himself. The controversy began when Nestorius (386-450), newly-installed as archbishop of Constantinople, sought to reform his congregation’s liturgy, by expunging from it all reference to Mary as the “God-bearer” (Theotokos). It was at best nonsense, Nestorius thought, to attribute an action such as “being born” to the person of God the Son, who is immutable by nature. He preferred instead to reason backwards from the distinct classes of actions in Christ – his human acts of weakness and suffering, his divine acts of healing and forgiving and saving – to two distinct agents, each manifesting his distinct nature, albeit perfectly united in will.

Nestorius’s nemesis was Cyril (376-444), the irascible archbishop of Alexandria. From Cyril’s standpoint, Nestorius’s Christology was fundamentally idolatrous, since it teaches that the man we worship isn’t really God, but only united to God, greater in degree but not different in kind from the biblical prophets. Where Nestorius began his reflections from the properties of the two natures of Christ, Cyril (particularly in his masterwork, On the Unity of Christ) began from the sole protagonist of the Gospels, God the Son himself, who assumed a complete human nature as his “sacred instrument,” and so infused every aspect of human life with his deity. This coincidence of the two natures in the person of the Logos allowed a “communion of attributes” to open up between Jesus’ divinity and humanity, so that we can properly speak of his blood as saving us, and of God as crucified.

The Council of Ephesus (431) quickly condemned Nestorius and affirmed the Virgin’s title of “Theotokos.” (The location was chosen in part for its historic associations with Mary, who was believed to have lived there with the Apostle John to the end of her days.) In the wake of Cyril’s death in 444, however, fierce debate arose around how best to continue his legacy, with a vocal minority insisting upon a “single-nature” (monophysite) interpretation of Cyril’s thought, according to which the two natures remained only conceptually distinct after the Incarnation. Monophysitism was eventually condemned at the Council of Chalcedon (451), which taught that Christ’s two natures are united “without confusion,” but also (against Nestorius) “immutably, indivisibly, inseparably.”

It’s perhaps significant that Article II, following the Augustana, remarks only that Christ’s natures are “never to be divided,” without adding Chalcedon’s balancing comment on their equally remaining “unconfused.” The Reformation saw a sharp revival of the Christological controversy in an intra-Protestant dispute over the nature of Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper, which pitted Zwingli and then Calvin, who insisted that Christ’s bodily ascension to the Father’s “right hand” precluded his bodily presence in the Eucharistic elements, against Luther, who (notably in his Treatise on the Lord’s Supper) drew on the “communion of attributes” to insist that Jesus’ human nature possessed divine properties such as ubiquity. For Luther, Zwingli was Nestorius redivivus, separating what God had joined, while the Swiss regarded Luther as a new and cruder Monophysite, confusing the natures. The Augsburg Confession’s particular focus on the dangers of “separating” the natures seems to reflect Luther’s concerns in this Eucharistic debate.

The final clauses of the Article follow the Apostles’ and Nicene Creed’s itinerary through the Passion, affirming Christ’s crucifixion, death, and burial. It glosses these events in two ways, first noting that Christ came “to reconcile us to the Father,” perhaps alluding to 2 Cor. 5:18 (“God…through Christ reconciled us to himself”), and second, insisting that Christ was a “sacrifice” “not only for original guilt, but also for actual sins.” This expression is clarified by its reappearance in Article XXXI, which attacks the Roman Catholic belief in “sacrifices of Masses” as “blasphemous fables,” since “the Offering of Christ once made is that perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction, for all the sins of the whole world, both original and actual.”

The view implicitly criticized here seems to be one in which Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is regarded as atoning for “original sin,” while the separate “sacrifices of Masses” atone for “actual sins” committed by Christians after baptism. In support of the view that this was in fact the Roman Catholic understanding of the Mass, Leif Graine cites the Council of Trent’s teaching that “that sacrifice [sc. the Mass] truly is propitiatory” (Sess. 22, ch. 2, quoted in Graine, The Augsburg Confession: A Commentary, 52n5).

However, Graine doesn’t quote the next sentence but one from this canon: “For the victim is one and the same, the same now offering by the ministry of priests, who then offered Himself on the cross, the manner alone of offering being different. The fruits indeed of which oblation, of that bloody one to wit, are received most plentifully through this unbloody one; so far is this (latter) from derogating in any way from that (former oblation).” This canon (solemnized in 1563) admittedly postdates the Augustana, but it also clearly applies the standard scholastic understanding of the sacraments’ relation to Christ’s Passion to the Mass itself; as Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) wrote, “the sacraments of the Church derive their power specially from Christ’s Passion, the virtue of which is in a manner united to us by our receiving the sacraments” (Summa Theologiae 3.62.5). It would go too far to say that there was nothing in 16th-century Catholicism which merited the Augustana’s criticism; but it goes equally too far to say that Catholicism’s dogmatic understanding of the sacrifice of the Mass is well-represented by it.

Brendan Case is a recent graduate of the Doctor of Theology program at Duke Divinity School, where he studied systematic and historical theology, with a particular focus on the high scholastics. He will begin work this fall as a postdoctoral Research Associate at Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion.